It’s not easy but it lies within

Within this exploration I take a

research-oriented perspective to look at the current global shift towards insularity and nationalistic

fervor, probing the complexities

and the challenges of engaging in dialogue

across divergent ideologies or viewpoints. In this first quarter of the 21st century, we face again numerous «isms» coming to the fore with the horrors of history and their inevitable connection

to produce the present.

Our inquiry investigates the boundaries that define us,

the remnants of memory

, the

echoes

of loss and trauma, the silent histories,

and the ways in which personal narratives are either immortalized or forgotten

within the acts of commemoration. The phenomenon of memories dissolving, yet

persisting in the individual and societal narrative, and our apparent failure

to learn from them to shape a more positive future, serves as a catalyst for a

deeper engagement with these themes.

A recent expression from my stepson during a talk encapsulates this sentiment succinctly:

« Your parents lived through the last war against Nazism in the sanctuary of Switzerland, your father was nineteen and in the same age as

I am today. And we both know Shoa survivors in our closest circle who endured unimaginable suffering. »

His remark, a blend of surprise and realization what history means has prompted a new understanding of the proximity of these events to our own lives.

A recent expression from my stepson during a talk encapsulates this sentiment succinctly:

« Your parents lived through the last war against Nazism in the sanctuary of Switzerland, your father was nineteen and in the same age as

I am today. And we both know Shoa survivors in our closest circle who endured unimaginable suffering. »

His remark, a blend of surprise and realization what history means has prompted a new understanding of the proximity of these events to our own lives.

On the other hand, Yuval Noah Harari’s recent works and interviews

present a challenging stance on the culture of remembrance, questioning our

approach to historical events.

«It is the best reason to learn history not in

order to predict the future but to free yourself from the past and Imagine

alternative destinies. People are caught up in the history, in the stories we

tell about the past.

Nevertheless I think we have to learn more history not in

order to remember what happened a hundred or 500 years ago and who did what to

whom but to be liberated from

«all this dead people from the past»

basically

holding captive our imagination, our mind, our feelings and forcing us to continue

their conflicts, their hatreds and their fears.»

This raises critical questions: Are the narratives too numerous or too scarce, and who claims ownership over them? Can we extricate these stories from the deep-seated pain of loss and trauma that runs through family lines? Is it feasible for an individual to forget these traumatic events, overshadowing the shared memories of entire nations, ethnic groups, and religious communities that have endured wars and atrocities, such as the Holocaust, the Armenian genocide, or the persecution of the Sinti and Roma?

The enormity of these losses and their ripple effects through generations is a profound topic of exploration, offering insights into the human condition and our collective history. Moreover, is it possible to acknowledge the simultaneous existence of greed and malevolence alongside the longing for peace and a better world? Do these stories contribute to our resilience, equipping us to face future challenges, and necessitate a constant state of defensive readiness? At this juncture, I seek to pose inquiries, provide fewer responses, yet nonetheless adopt a personal artistic stance and position and trying to unravel the complex web of human experience interlaced with memory, loss, and the perpetual pursuit of peace.

This raises critical questions: Are the narratives too numerous or too scarce, and who claims ownership over them? Can we extricate these stories from the deep-seated pain of loss and trauma that runs through family lines? Is it feasible for an individual to forget these traumatic events, overshadowing the shared memories of entire nations, ethnic groups, and religious communities that have endured wars and atrocities, such as the Holocaust, the Armenian genocide, or the persecution of the Sinti and Roma?

The enormity of these losses and their ripple effects through generations is a profound topic of exploration, offering insights into the human condition and our collective history. Moreover, is it possible to acknowledge the simultaneous existence of greed and malevolence alongside the longing for peace and a better world? Do these stories contribute to our resilience, equipping us to face future challenges, and necessitate a constant state of defensive readiness? At this juncture, I seek to pose inquiries, provide fewer responses, yet nonetheless adopt a personal artistic stance and position and trying to unravel the complex web of human experience interlaced with memory, loss, and the perpetual pursuit of peace.

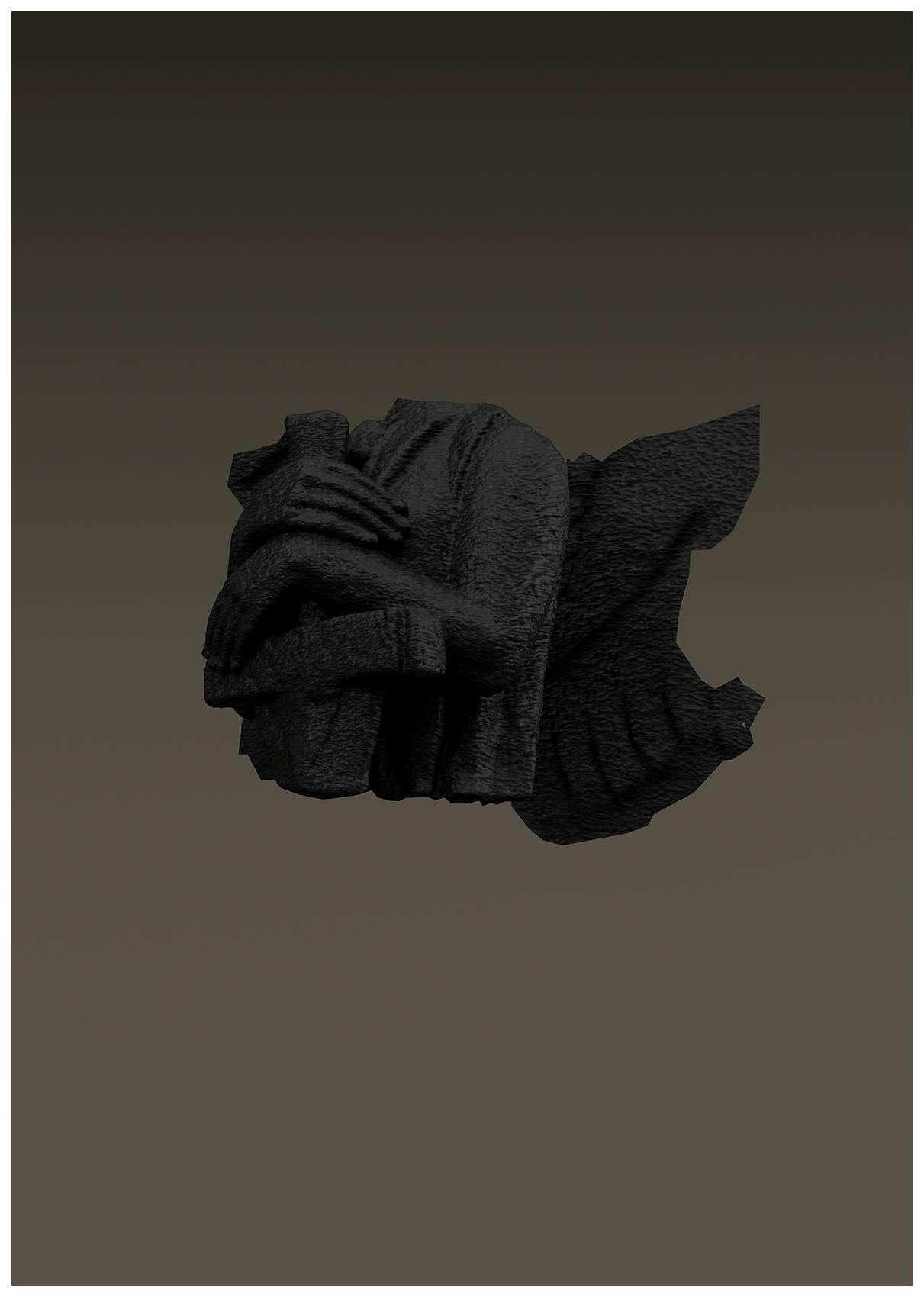

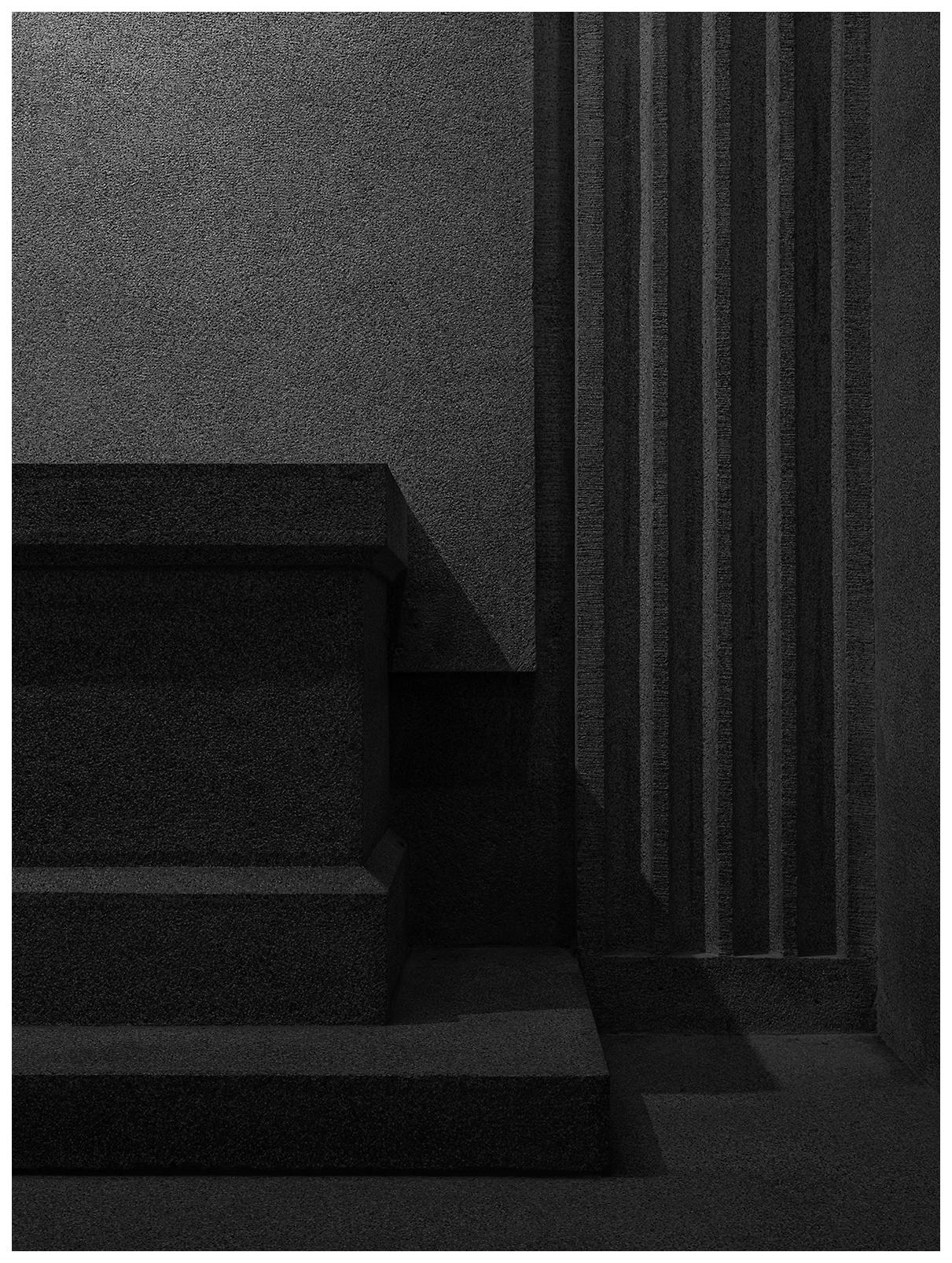

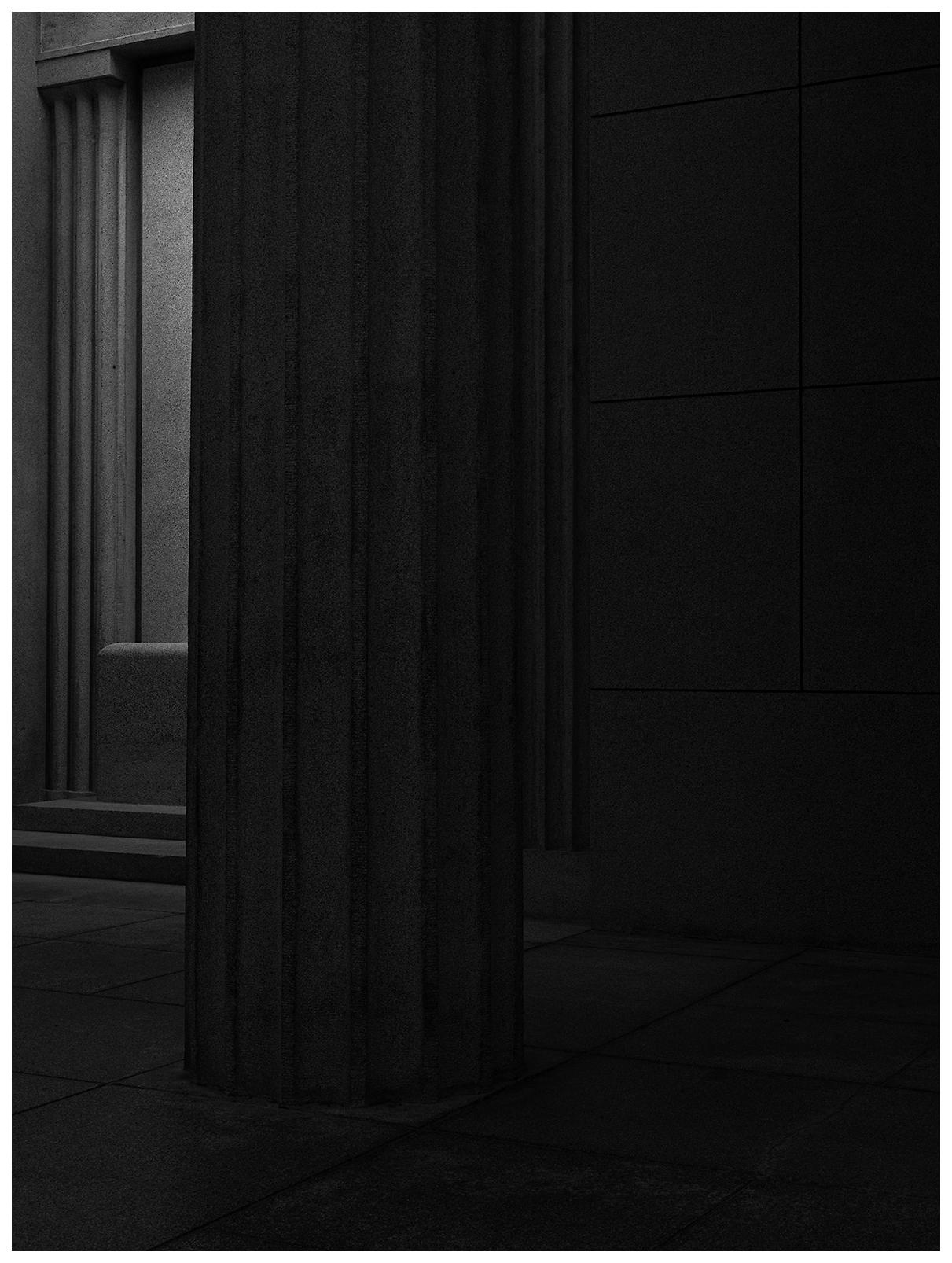

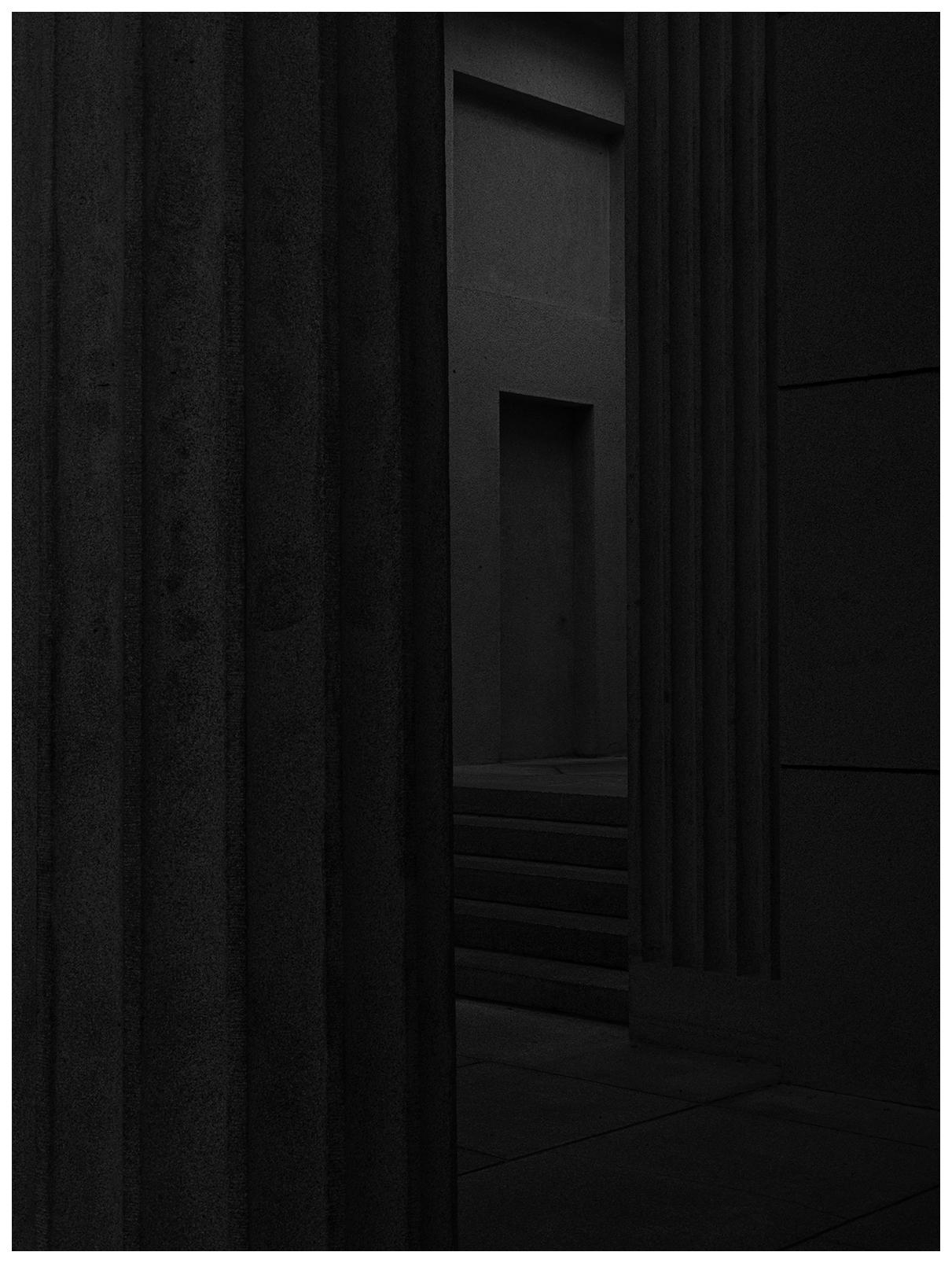

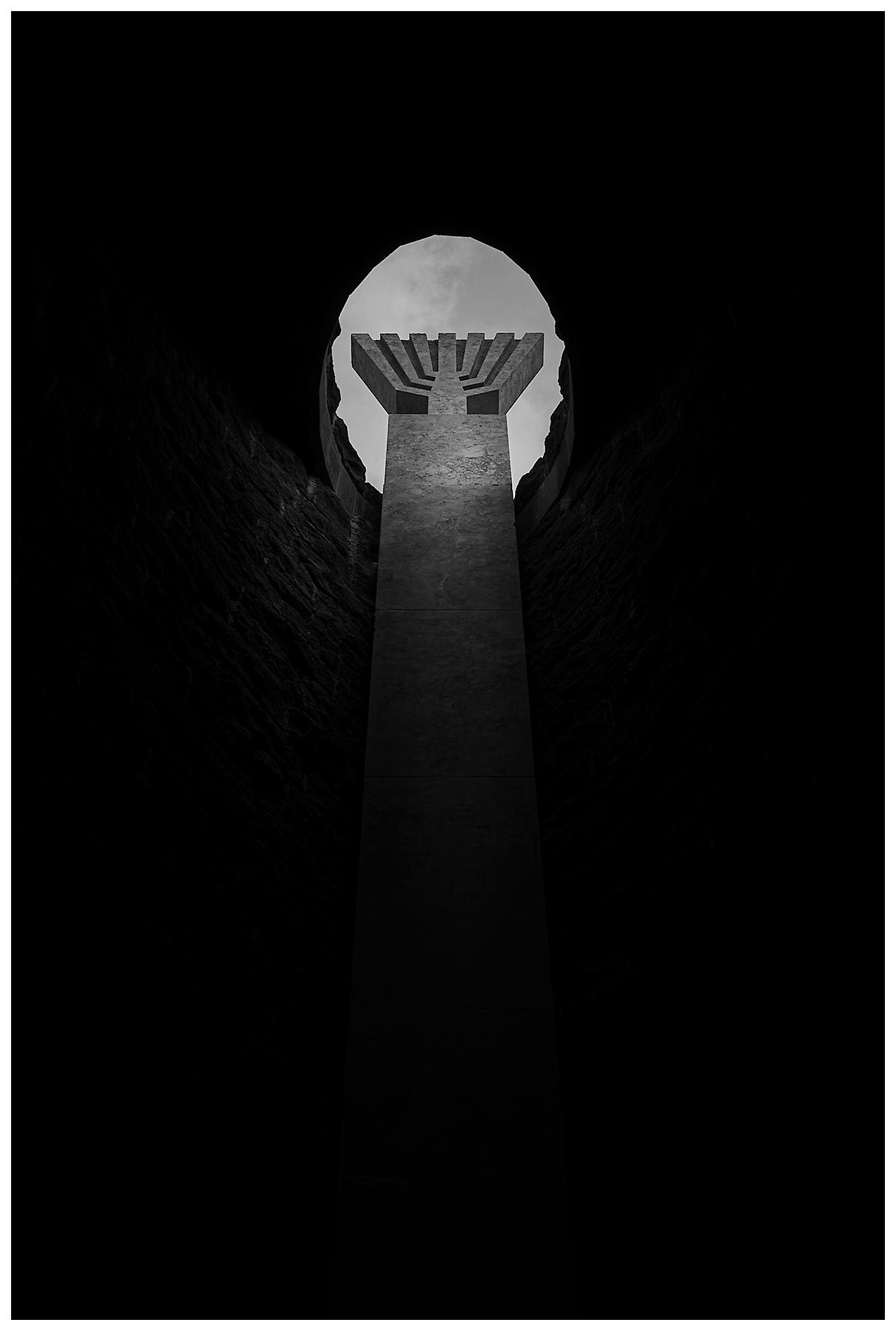

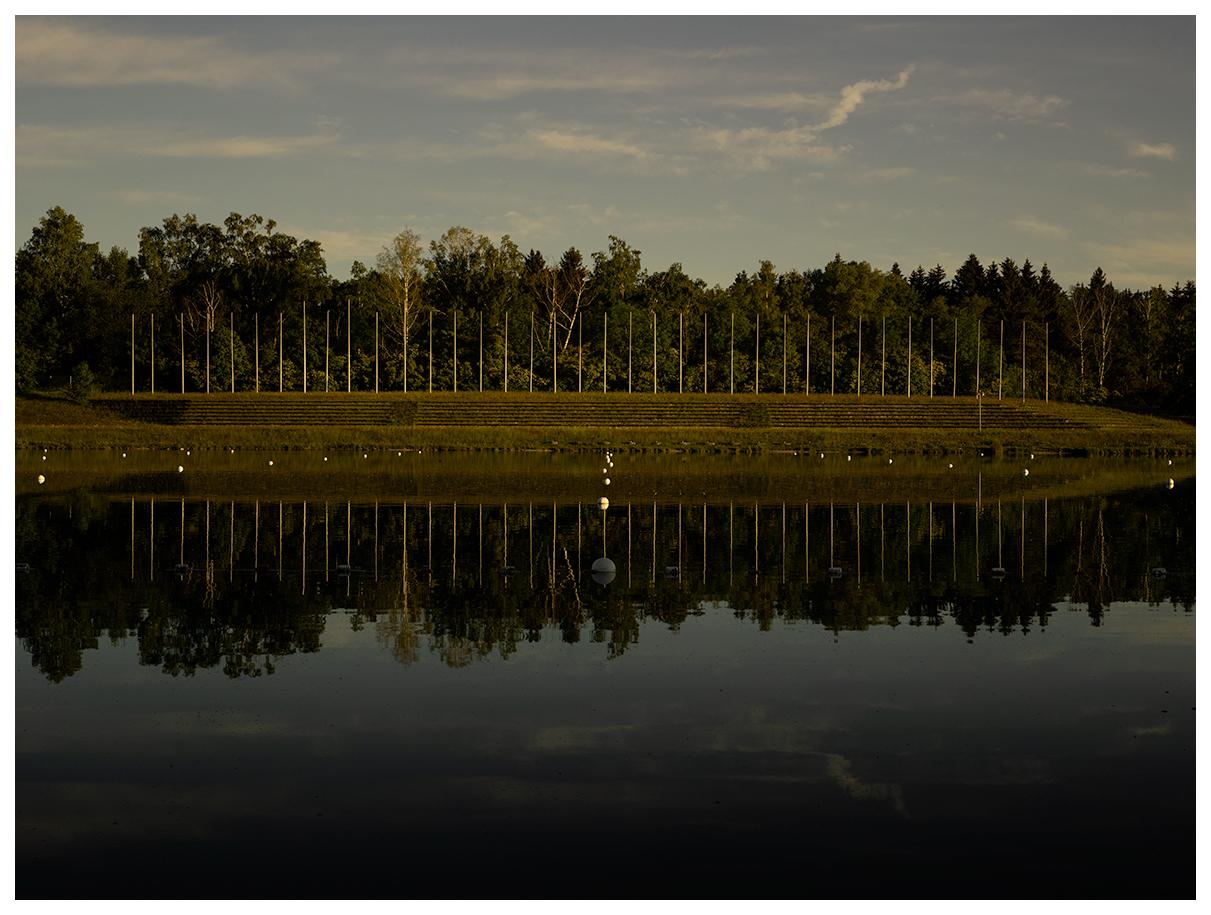

Delusion

Delusion confronts us with thinking about the tragic consequences of nationalist ideologies. In doing so, I illuminate places that have become symbols of delusion and mass death - places where young men, often no older than twenty, were drawn into the vortex of war by the seductive and destructive forces of nationalism. These men, thrown into the “meat grinder” of conflict, are representative of millions sacrificed in the turmoil of history.

The cycle is intended to tell the story of the anonymity of the individual in an encrypted way in the face of mass destruction and the dehumanization that wars bring with them. They pay homage to the countless lives extinguished in the trenches and on the battlefields and serve as a cautionary reminder of the fragility of peace. In doing so, I invite you to reflect on the meaning of these places today and how they shape our collective memory and our future and try to establish a dialogue between the past and the present, remembering that the lessons of history do not may be forgotten.

It conveys the idea that the places themselves serve as silent observers

of the past, preserving their stories even when they are no longer openly revealed.

The cycle is intended to tell the story of the anonymity of the individual in an encrypted way in the face of mass destruction and the dehumanization that wars bring with them. They pay homage to the countless lives extinguished in the trenches and on the battlefields and serve as a cautionary reminder of the fragility of peace. In doing so, I invite you to reflect on the meaning of these places today and how they shape our collective memory and our future and try to establish a dialogue between the past and the present, remembering that the lessons of history do not may be forgotten.

It conveys the idea that the places themselves serve as silent observers

of the past, preserving their stories even when they are no longer openly revealed.

The images are intended to represent a visual synthesis

and create an imagery that stimulates thought and invites viewers to take

a new look at the past and question its meaning for the present.

«The Hun is going to get consummate hell.»

The Guardian, June 30 2016

«The Hun is going to get consummate hell.»

The Guardian, June 30 2016

on the 12th of October, when he was actually lying on the battlefield

mortally wounded:

«Who knows but that we may meet again in another sphere, when I shall be able to thank you personally for everything?

»

These battlefields, now silent, were once filled with the cacophony of gunfire and the cries of the fallen. Young men, many scarcely older than boys, were drawn into the vortex of nationalism and sacrificed on the

altar of empires. They marched to the front, hearts ablaze with fervor, only to be consumed by the inferno of conflict.

At Hartmannswillerkopf, the rugged terrain of the Vosges Mountains bore witness to the relentless struggle for control. The French and German armies clashed amidst the snow and stone, each inch of ground soaked with the blood of delusioned patriots. The Somme, with its rolling hills and tranquil rivers, became a stage for one of the bloodiest battles in human history, where the earth itself was churned into a morass of mud and metal. Ypres, saw first time in history the horrors of chemical warfare. The town and its surroundings, once a tapestry of pastoral beauty, were transformed into a hellscape of craters and barbed wire.

All these places of death famous and synonymous with the war’s brutality, saw soldiers from across the globe confront the horrors of warfare and incessant bombardment. And there were so many.

In the end, the First World War was not only a clash of nations but a crucible that forged the modern age. It was a tragedy that unfolded on

a global stage, leaving a legacy of grief and courage that continues to inspire and haunt us to this day.

Since the onset of 2023, we are witnessing an intra-European war between Russia and Ukraine for the first time since more then seven decades. What was previously unimaginable for various reasons has,

by mid-2024, transformed into a war of positions reminiscent of the last such conflict we saw during World War I - with trenches and man-to-man combat, sometimes within shouting distance.

From the Trenches: Reflections on the Great War’s Theatres of Valor

Anthony Richards, head of documents and sound at the museum, said although the soldiers were issued with cloth

or paper ID tags, some made their own for fear of ending up – as so many did – an unidentifiable corpse in a mass grave.

Many were not formal last letters. Thomas Farlam wrote cheerfully in September to ask his wife for a notebook.

Annie’s letter, stained with the Somme mud, was found

among his possessions after his death on 16 September.

Royston Jones wrote on 10 September to his parents,

Amelia and Charles, at home in Hackney, east London, assuring them that he was «quite in the pink» and had

got their parcel. He ended:

« I want some safety razor blades as soon as poss as

I have run out of them also. »

Five days later he was dead, aged 20.

or paper ID tags, some made their own for fear of ending up – as so many did – an unidentifiable corpse in a mass grave.

Many were not formal last letters. Thomas Farlam wrote cheerfully in September to ask his wife for a notebook.

Annie’s letter, stained with the Somme mud, was found

among his possessions after his death on 16 September.

Royston Jones wrote on 10 September to his parents,

Amelia and Charles, at home in Hackney, east London, assuring them that he was «quite in the pink» and had

got their parcel. He ended:

« I want some safety razor blades as soon as poss as

I have run out of them also. »

Five days later he was dead, aged 20.

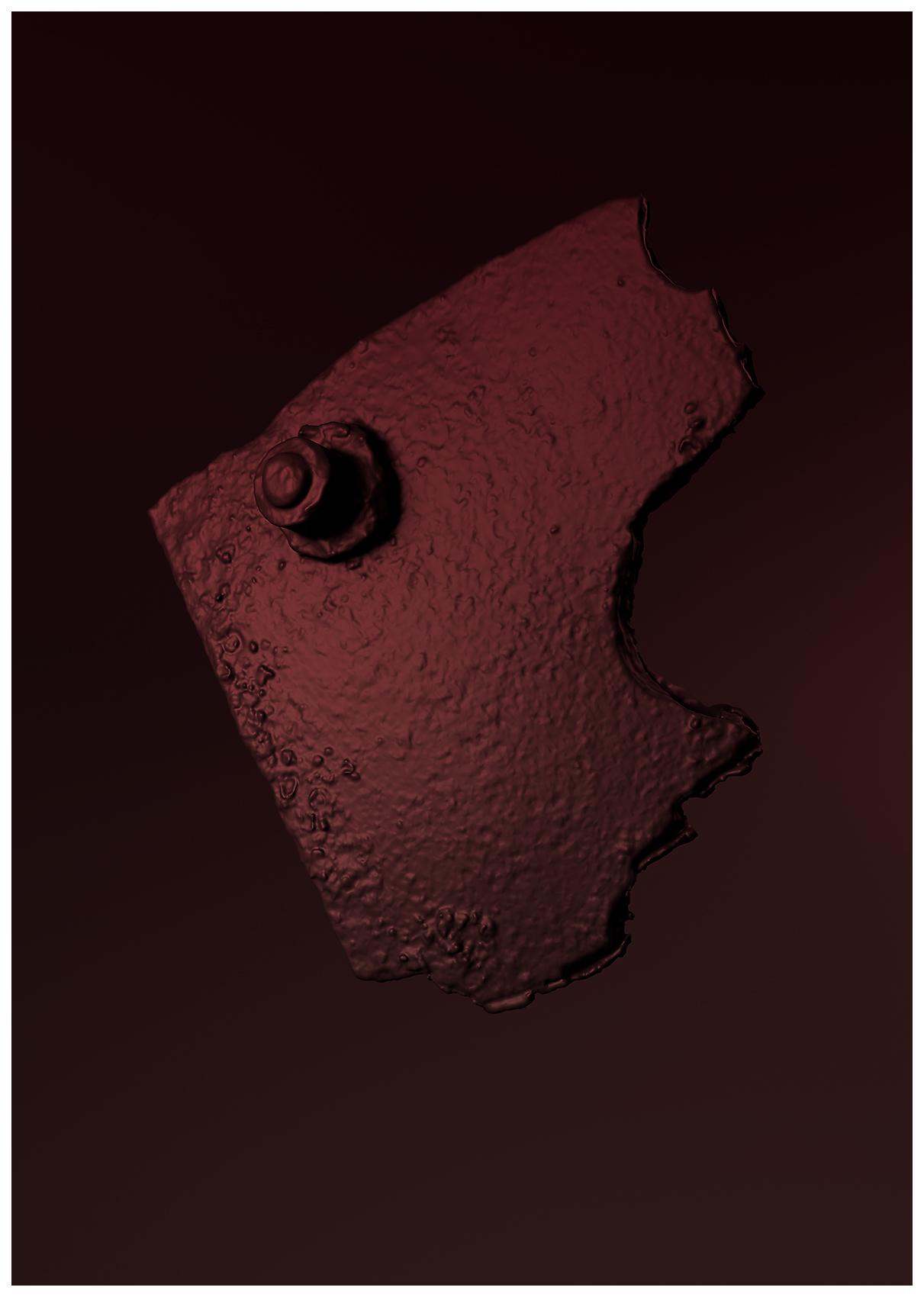

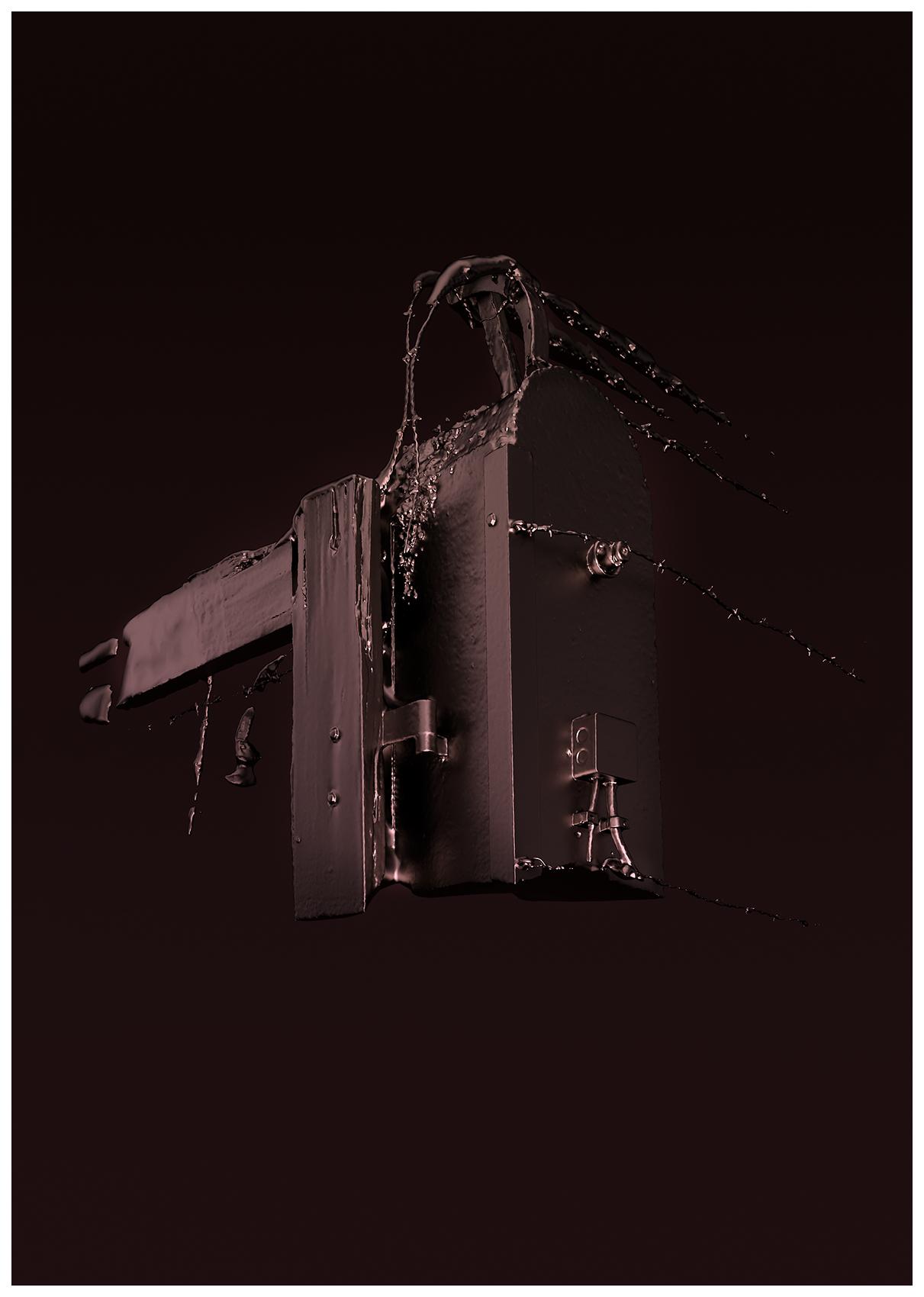

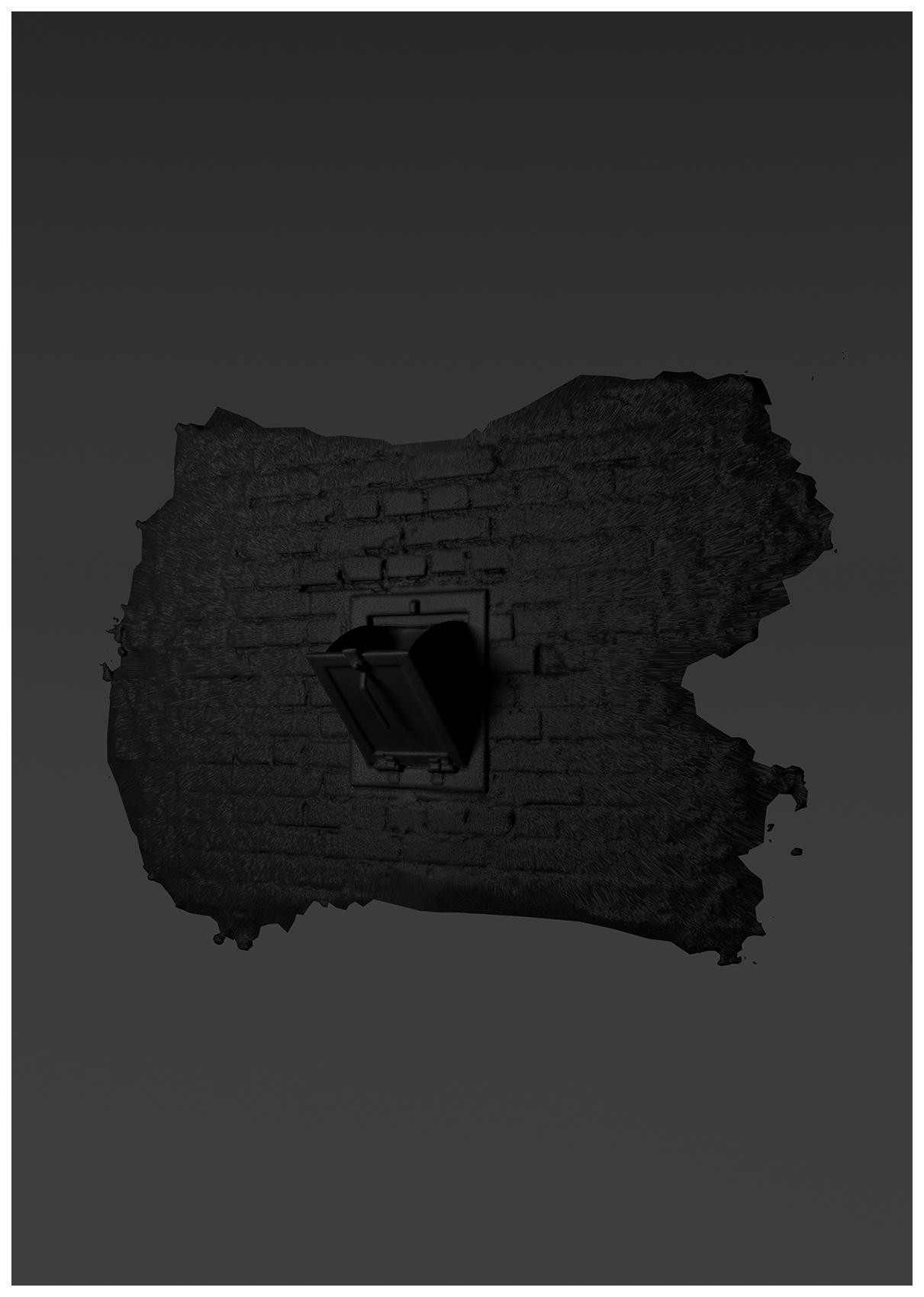

Poison

The cycle offers a subtle yet powerful reflection on the victims of genocide. In this collection, commemoration is presented as a dynamic process that calls on us to continually engage with the past. The images are contributions that emphasize the need to keep the memory of the tragedies of history alive and to learn from them. It is intended to be a critical examination of the depths of human cruelty and hatred, to create an emotional resonance that leads to a critical discourse about the Horrors of the past and their implications for the present.

«We must be very caution and

paying attention to the canary in

the coal mine.»

paying attention to the canary in

the coal mine.»

The events of October 7, 2023 in Israel and the aftermath around the world starting on the very same day made us painfully aware that silence and anti-Semitism are still present and are returning with frightening intensity.

«The hate that begins with Jews

never ends with Jews.»

I am calling on you never to choose silence, but rather to stand up courage-ously for humanity, an appeal to our collective consciousness

to see history not as a distant chronicle, but as a living lesson that calls

us to be vigilant and responsible for the future take over. Justice and humanity are values that must always be defended and that remem-bering the past is a key to preventing such tragedies from repeating themselves in the future.

The “Poison” cycle is intended to be a plea for humanity and a small contribution against forgetting and inactivity against evil.

The final artifacts are large-format photographs that hint but do not reveal, accuse but are not overtly loud. They are images that we perceive as kind of decorative elements without the explanatory momentum, thus carrying a form of innocence - however, their scope and depth only become apparent in context and title.

.

.

zweite Variante

It lies within (Project Draft, Working title)

Within this exploration I take a research-oriented perspective to look at the current global shift towards insularity and nationalistic fervor, probing the complexities and the challenges of engaging in dialogue across divergent ideologies or viewpoints. In the first quarter of the 21st century, we face again numerous «isms» coming to the fore with the horrors of history and their inevitable connection to produce the present. Our inquiry investigates the boundaries that define us, the remnants of memory , the echoes of loss and trauma, the silent histories, and the ways in which personal narratives are either immortalized or forgotten within the acts of commemoration. The phenomenon of memories dissolving, yet persisting in the individual and societal narrative, and our apparent failure to learn from them to shape a more positive future, serves as a catalyst for a deeper engagement with these themes.

On the other hand, Yuval Noah Harari’s recent works and interviews present a challenging stance on the culture of remembrance, questioning our approach to historical events. «It is the best reason to learn history not in order to predict the future but to free yourself from the past and Imagine alternative destinies. People are caught up in the history, in the stories we tell about the past. Nevertheless I think we have to learn more history not in order to remember what happened a hundred or 500 years ago and who did what to whom but to be liberated from «all this dead people from the past» basically holding captive our imagination, our mind, our feelings and forcing us to continue their conflicts, their hatreds and their fears.»

On the other hand, Yuval Noah Harari’s recent works and interviews present a challenging stance on the culture of remembrance, questioning our approach to historical events. «It is the best reason to learn history not in order to predict the future but to free yourself from the past and Imagine alternative destinies. People are caught up in the history, in the stories we tell about the past. Nevertheless I think we have to learn more history not in order to remember what happened a hundred or 500 years ago and who did what to whom but to be liberated from «all this dead people from the past» basically holding captive our imagination, our mind, our feelings and forcing us to continue their conflicts, their hatreds and their fears.»

This raises critical questions: Are the narratives too numerous or too scarce, and who claims ownership over them? Can we extricate these stories from the deep-seated pain of loss and trauma that runs through family lines? Is it feasible for an individual to forget these traumatic events, overshadowing the shared memories of entire nations, ethnic groups, and religious communities that have endured wars and atrocities, such as the Holocaust, the Armenian genocide, or the persecution of the Sinti and Roma?

The enormity of these losses and their ripple effects through generations is a profound topic of exploration, offering insights into the human condition and our collective history. Moreover, is it possible to acknowledge the simultaneous existence of greed and malevolence alongside the longing for peace and a better world? Do these stories contribute to our resilience, equipping us to face future challenges, and necessitate a constant state of defensive readiness? At this juncture, I seek to pose inquiries, provide fewer responses, yet nonetheless adopt a personal artistic stance and position and trying to unravel the complex web of human experience interlaced with memory, loss, and the perpetual pursuit of peace.

The enormity of these losses and their ripple effects through generations is a profound topic of exploration, offering insights into the human condition and our collective history. Moreover, is it possible to acknowledge the simultaneous existence of greed and malevolence alongside the longing for peace and a better world? Do these stories contribute to our resilience, equipping us to face future challenges, and necessitate a constant state of defensive readiness? At this juncture, I seek to pose inquiries, provide fewer responses, yet nonetheless adopt a personal artistic stance and position and trying to unravel the complex web of human experience interlaced with memory, loss, and the perpetual pursuit of peace.

Delusion

Delusion confronts us with thinking about the tragic consequences of nationalist ideologies. In doing so, I illuminate places that have become symbols of delusion and mass death - places where young men, often no older than twenty, were drawn into the vortex of war by the seductive and destructive forces of nationalism. These men, thrown into the “meat grinder” of conflict, are representative of millions sacrificed in the turmoil of history.

The cycle is intended to tell the story of the anonymity of the individual in an encrypted way in the face of mass destruction and the dehumanization that wars bring with them. They pay homage to the countless lives extinguished in the trenches and on the battlefields and serve as a cautionary reminder of the fragility of peace. In doing so, I invite you to reflect on the meaning of these places today and how they shape our collective memory and our future and try to establish a dialogue between the past and the present, remembering that the lessons of history do not may be forgotten.

It conveys the idea that the places themselves serve as silent observers

of the past, preserving their stories even when they are no longer openly revealed.

The images are intended to represent a visual synthesis and create an imagery that stimulates thought and invites viewers to take a new look at the past and question its meaning for the present.

The cycle is intended to tell the story of the anonymity of the individual in an encrypted way in the face of mass destruction and the dehumanization that wars bring with them. They pay homage to the countless lives extinguished in the trenches and on the battlefields and serve as a cautionary reminder of the fragility of peace. In doing so, I invite you to reflect on the meaning of these places today and how they shape our collective memory and our future and try to establish a dialogue between the past and the present, remembering that the lessons of history do not may be forgotten.

It conveys the idea that the places themselves serve as silent observers

of the past, preserving their stories even when they are no longer openly revealed.

The images are intended to represent a visual synthesis and create an imagery that stimulates thought and invites viewers to take a new look at the past and question its meaning for the present.

Poison

«We must be very caution and

paying attention to the canary

in the coal mine.»

paying attention to the canary

in the coal mine.»

The cycle offers a subtle yet powerful reflection on the victims of genocide. In this collection, commemoration is presented as a dynamic process that calls on us to continually engage with the past. The images are contributions that emphasize the need to keep the memory of the tragedies of history alive and to learn from them. It is intended to be a critical examination of the depths of human cruelty and hatred, to create an emotional resonance that leads to a critical discourse about the Horrors of the past and their implications for the present.

The series “Poison” addresses this topic indirectly and conveys powerfully that the fight against hatred and discrimination is an ongoing obligation. I try to show that there is no finality in the fight against such anti-human attitudes - it is a continuous process that requires and demands our constant commitment and vigilance.

I am calling on you never to choose silence, but rather to stand up courage-ously for humanity, an appeal to our collective consciousness

to see history not as a distant chronicle, but as a living lesson that calls

us to be vigilant and responsible for the future take over. Justice and humanity are values that must always be defended and that remem-bering the past is a key to preventing such tragedies from repeating themselves in the future.

The “Poison” cycle is intended to be a plea for humanity and a small contribution against forgetting and inactivity against evil.

The final artifacts are large-format photographs that hint but do not reveal, accuse but are not overtly loud. They are images that we perceive as kind of decorative elements without the explanatory momentum, thus carrying a form of innocence - however, their scope and depth only become apparent in context and title.

«The hate that begins with Jews never ends with Jews.»

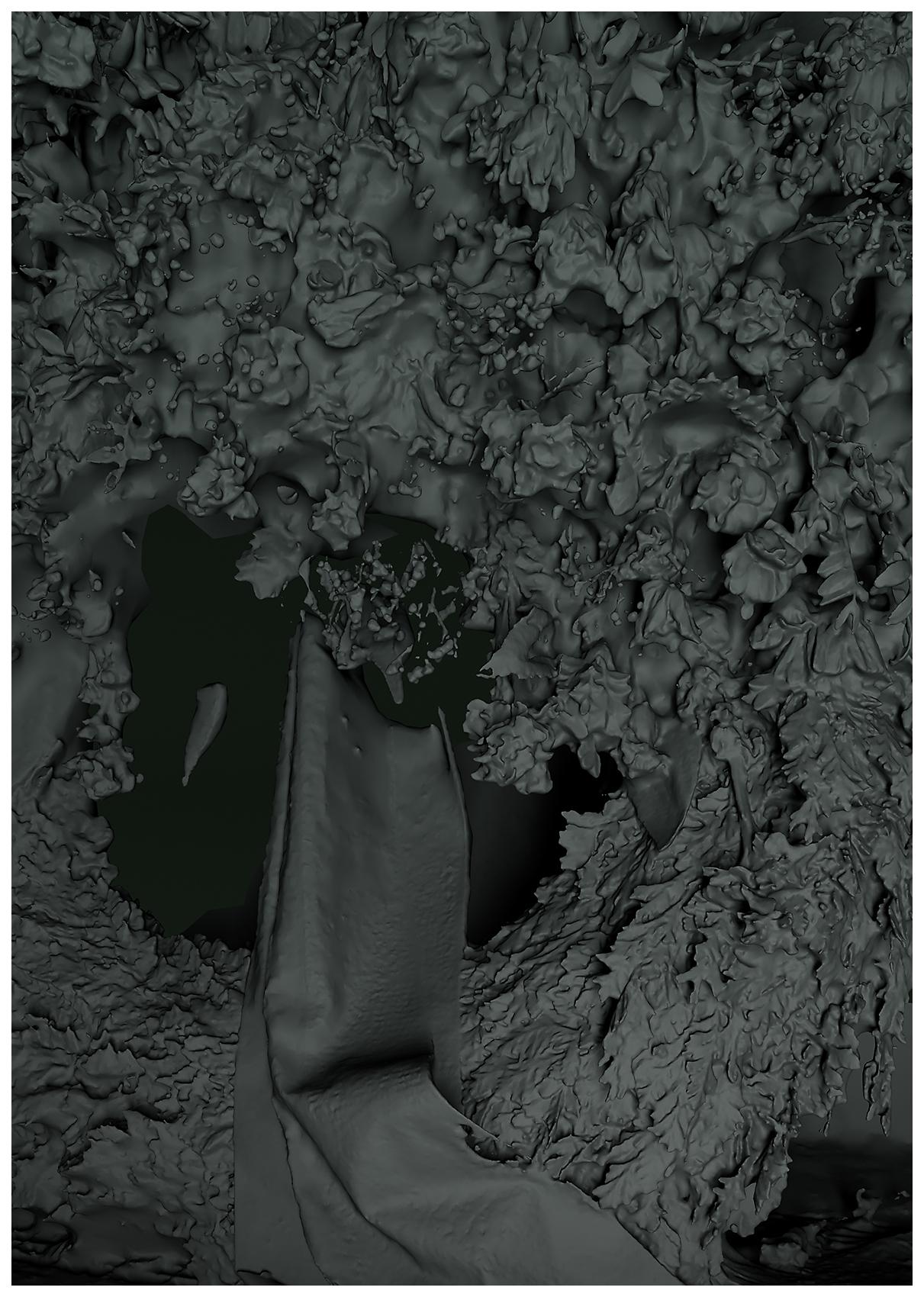

A significant photographic aspect of my work involves the

exploration and translation of visual memory, both within

the scenographic-architectural context related to individual

thematic areas and through directly historical artifacts or

sculptures and their impact, artistically, psychologically,

and as a societal element of identity formation.

A significant photographic aspect of my work involves the

exploration and translation of visual memory, both within

the scenographic-architectural context related to individual

thematic areas and through directly historical artifacts or

sculptures and their impact, artistically, psychologically,

and as a societal element of identity formation.

Reflections on the visuality of rememberance

Reflections on the visuality of rememberance